Reclaiming History

— Parks, Caching, and a Woman Named Kiyo

When traveling, we often have relied on our national parks to help us learn about the history of an area. Some of that history is sad, some of it is inspiring, and it can be both. As long as humans make history, it will show all aspects of human behavior.

This is changing. On March 27, 2025, Trump issued an executive order “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History.” Agencies were directed to restore monuments that had been removed and to ensure that exhibits “do not contain descriptions, depictions, or other content that inappropriately disparage Americans past or living.” The Smithsonian was also directed to remove “divisive, race-centered ideology.” Interior Secretary Burgum ordered all national parks to post signs asking visitors to report any information that tells a negative story about the site or its history.

In a social media post on August 19, Trump complained about what he called excessive focus on “how bad Slavery was.” He emphasized, “This Country cannot be WOKE, because WOKE IS BROKE.”

In a social media post on August 19, Trump complained about what he called excessive focus on “how bad Slavery was.” He emphasized, “This Country cannot be WOKE, because WOKE IS BROKE.”

The Interior Department has already made significant changes to history, such as removing trans participation from the Stonewall National Monument that recognized a turning point in the LBGTQ movement.

In September, The Washington Post reported that the Trump administration has already ordered the removal of exhibits related to slavery at multiple parks. The sites affected included Harpers Ferry in West Virginia (where John Brown fought against slavery) and the President’s House Site in Philadelphia.

Muir Woods removed an exhibit that was based on sticky notes that were on a permanent sign. The notes added context to the park’s history, highlighting the roles of women and the history of indigenous people. Other signage removed have included the effects of climate change, the treatment of Native Americans, and Japanese internment

KQED reports that reactions among park workers ranged from disbelief to anger. One park superintendent stated “Sometimes I’m raging. Sometimes I’m in denial.” The danger, however, is apparent. One ranger put it simply, “You silence the voices that are inconvenient to you, and you control history, you control the narratives.”

The Organization of American Historians agrees. It warned that the Executive Order “proposes to rewrite history to reflect a glorified narrative that downplays or disappears elements of America’s history — slavery, segregation, discrimination, division — while suppressing the voices of historically excluded groups.”

We can celebrate the ideals of our country and recognize that history often does not reflect them. Indeed, it is impossible to make the genocide of Native Americans, slavery, and other events look positive. At the same time, the ways that people have organized themselves, relied on their faith, and created movements that have changed the country are inspiring. Can we really pretend that Wounded Knee and the Trail of Tears do not exist?

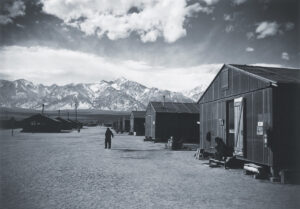

Manzanar is such a place, one we are in danger of forgetting. It was an internment camp in World War 2 that held up to 10,000 people of Japanese ancestry. A virtual cache explains that “is not for those seeking a physically beautiful place. It is dusty and hot in summer and snow-covered in winter. However, if you want to experience a meaningful and important historic site, you should definitely make this trip.”

It was particularly important for me because one of my teachers had been imprisoned there. We knew very little of her story. My parents told me she had been imprisoned there but it was never mentioned at school. We weren’t even taught about it.

Her intake form states that arrived at Manzanar with BA degrees in social science and math. It states that she might be employed as a semiskilled dressmaker or seamstress. She had never been to Japan. Her camp number was 03023A. She became a student teacher there.

It is a site where Trump’s executive order might be impossible to completely fulfill. As long as there are traces of the camp it will endure, but how it is taught is at risk. It would not take much to present a history that removes the pain people felt. A changed paragraph here and there would be enough. Ultimately what people might experience there depends on those of us who visit, and affirm the importance of truth.

If you have come there to cache, there is an attendant responsibility to protect it. The same can be said about other places where I have cached — from Wounded Knee to slave cemeteries or statue of Elizabeth Freeman, a slave who sued to become free. If you know the truth you have to defend it. It’s that simple.

At its best, the very act of geocaching stands against those who would want us to forget history. It is here where we can find places that are important to remember, to tell our own stories, and to share our memories. A long memory is an important defense against those who want to change what we know to be true. When history is being washed away, we must reclaim it and never forget.

“Any attempt to constrain or sanitize the stories that are told at Manzanar should concern every American,” said Naomi Ostwald Kawamura, executive director of Densho, an organization that documents the testimonies of Japanese Americans who were held in concentration camps. “I’m incredibly disappointed that this is happening in the United States because museums, monuments and memorials are public spaces where we can explore difficult history, confront our past, engage with what’s uncomfortable and then be able to imagine the future that we want to collectively share.”

— Victoria Namkung, The Guardian, June 26, 2025

My Log

I once had a teacher who was imprisoned at Manzanar — the only family that was “relocated” from the town where I grew up. I knew her a little outside of class, but she never spoke about it to me. How could you not carry those memories every day? They would haunt your sleep. Even her silence about her experience was not something I forgot. I have long wanted to come to this place.

There are only a few remains of the camp from those times. Still, even the starkness of the cement slabs is a reminder that history cannot be buried. There are water works, a few graves that were never moved. Out of those traces came an unforgettable memorial.

Things were desolate at the camp. Hot and dusty in the summer. Cold in the winter. The sagebrush marked the seasons. One inmate wrote, “ In the winter, the sparsely rationed oil didn’t adequately heat the tar paper-covered pine barracks with knotholes in the floor. The wind would blow so hard, it would toss rocks around.” There was little or no privacy. And always, the towers.

The camp was in sharp contrast to what she had known before. Her father had operated a lemon orchard. The valley where we lived had been used in a movie to portray Shangri-iLa, an earthy paradise from Lost Horizon. And yet they endured. Her brother had enlisted before the war and helped liberate Dachau. The irony was probably not lost.

We walked down the rows where buildings once stood. Imagination might be helpful to comprehend how it looked, but the one thing that needs no imagination is Executive Order 9066, the order for internment. That is all too real. Fear, hatred, the other — we still feel the things that led us to imprison a people. It was approved by the highest court and was all too legal. The camp here suddenly does not seem all that far away.

Some resisted. A riot had to be put down. Some tried to make the most of things and planted gardens or improved the camp. Some joined the military. She started student teaching. After the war, she became a beloved math teacher.

I hope that this place will strengthen our resolve to never let such things happen again, but equally important, to confront why it happened in a way that does not consign it to mere history. It’s assumptions remain with us.

So I honor Kiyo Fukasawa. Although some might be surprised that I had a math teacher, she was one of the best, as a teacher and a person. Remember her along with the 10,000 who were here, and the 120,000 imprisoned in a concentration camp. There is so much I wish I had asked her.

Her name was Kiyo. She should not be forgotten.

(04/19/2015))